- Current projects

- Selected Works

- Häutungen und Metamorphosen

- Ex vivo - in vitro

- Sammlung Reinking Hamburg 2011

- Kunstmuseum Bern 2013

- Kunsthaus Zofingen 2017

- Mess Up Your Mind

- Mon crâne retrouve son propre visage

- Kunstgeschichte kitzelt

- Ataraxie & Eudaimonia

- Choreography Bern Ballett 2007

- Kunsthalle Bern 2006

- Aargauer Kunsthaus 2021

- Ali Baba und die 40 Kunstkritiker

- Alphons Silbermann 1999

- Art and War 2003

- Weserburg Bremen 2014

- Kunstverein Ruhr 2015

- Echo and Narcissus 2012

- Facing History 2019

- Rede mit mir

- The Artist

- Bibliography

- Lectureships

- Contact

Christine Breyhan, Infinite Performance, artist talk with Frantiček Klossner, published in Kunstforum International, vol. 228, 2014, on the occasion of the exhibition "Existenzielle Bildwelten / Sammlung Reinking", Museum für moderne Kunst Weserburg Bremen, 2014-2015

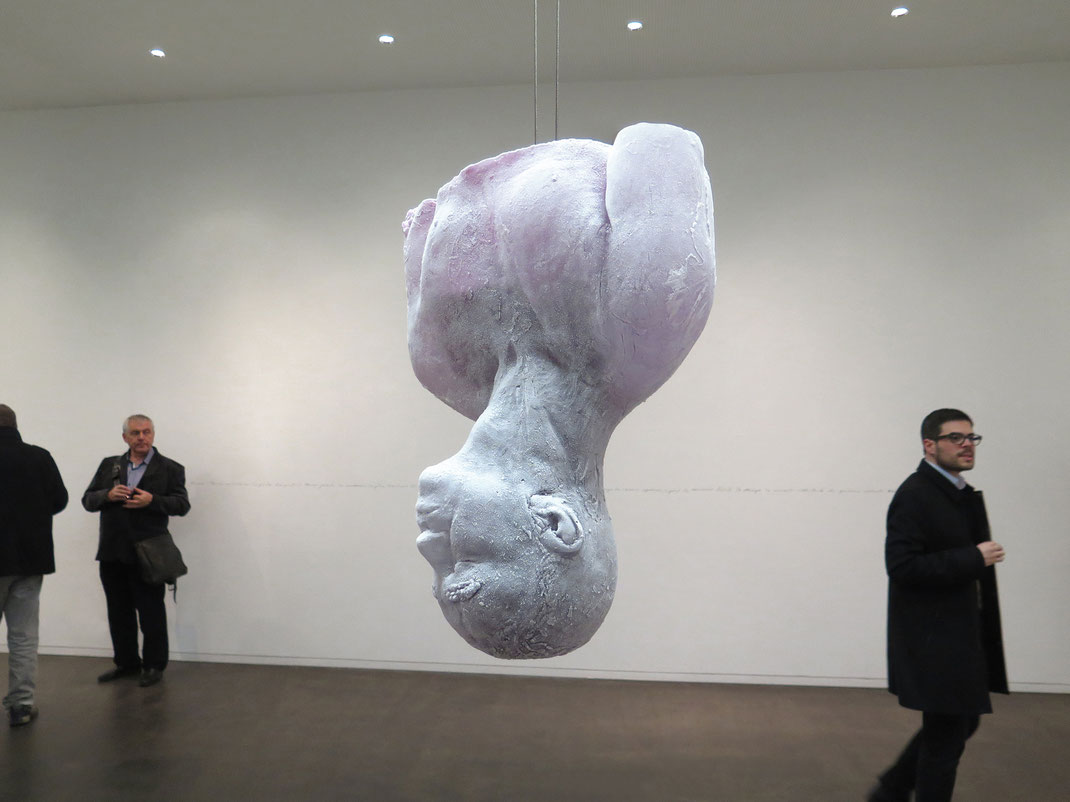

Frozen Self-Portraits

Christine Breyhan: The element of water - in all of its aggregate states - plays a key role in your works, and you have been working specifically with ice since the 1980s. You began with transient environments for performances or installations in public space. Figurative works featuring your frozen portrait followed in 1990: Melting Selves and Infinite Performance. Presented hanging upside-down in numerous exhibitions, they offer viewers an opportunity to observe the unstoppable process of melting away. They are products of transition: melting, freezing, melting away. Are you a kind of Sisyphus in search of passing time?

Frantiček Klossner: The term “infinite performance” is a very apt characterization of the series of works featuring my “melting self.” Process, presence, and dynamic in space are significant aspects of the work. As if in a kind of intimate ritual, I allow my head to melt again and again in different constellations. As the performer, the frozen self becomes my substitute. The single moment is celebrated and placed at the center of attention in numerous exhibitions and shifting contexts. Kairos defeats Chronos. The opportunities and the fascination of the moment take precedence over the passage of time.

CB: That brings us to your current exhibition here at the Kunstverein Ruhr: KAIROS UND CHRONOS. You refer to the perception of time and to the experience of the here and now. All of the senses are challenged in the process. What is the significance of visual energy?

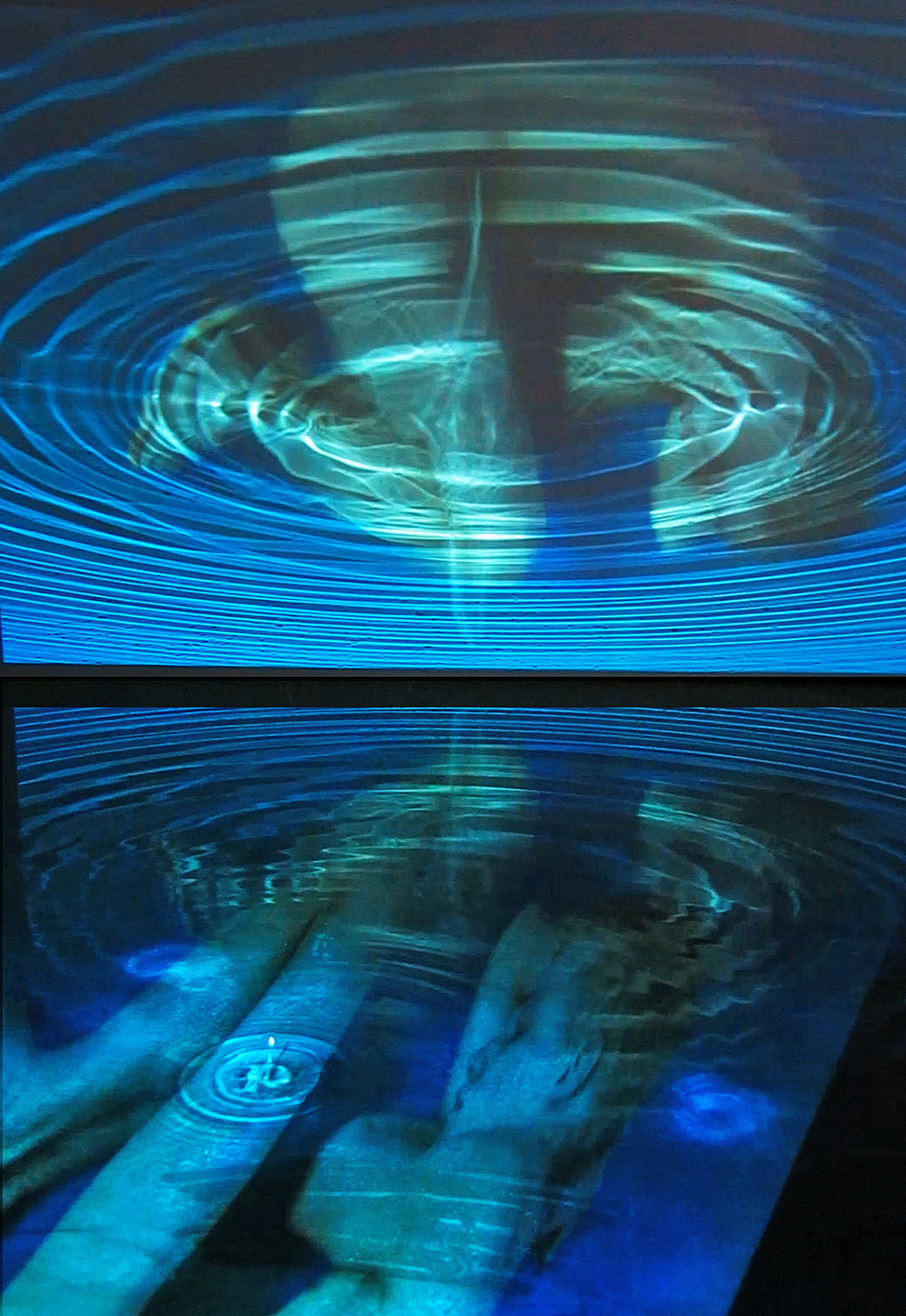

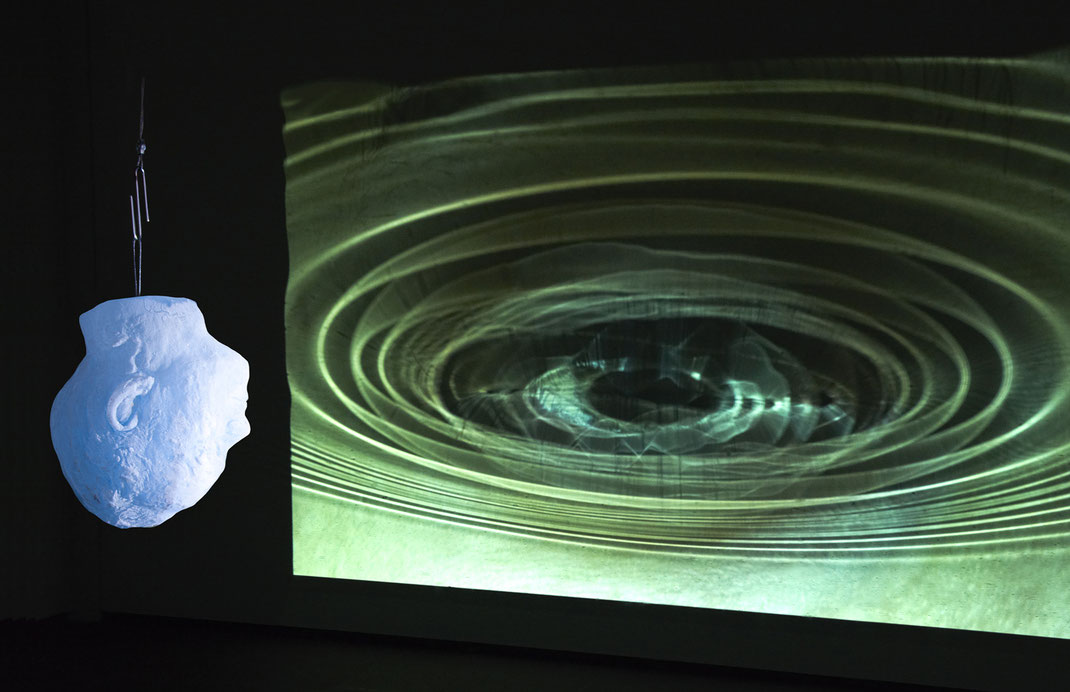

FK: Visual energy and direct interaction between the work and the viewers are essential aspects of all of my works. The presentation in the form of a performance involves viewers in a very physical dialog. The video installation I’m showing here in Essen exhibits this characteristic with particular clarity. Viewers feel lured into perception by the work. The fact that visual energy is experienced as part of the performative encounter is attributable to the fact that the other feels directly involved. There is no afterwards, for afterwards the work is already something different. That activates Kairos within us, the little god of the moment, the hopeful opponent of Chronos ... Kairos challenges us. Now or never! We seize the chance. Kairos, the ideal point in time, the moment of decision, becomes clearly palpable in this exhibition. My “frozen self,” a melting head made of ice, hangs above a square pool of water. Projected in alternation onto the water and reflected from there onto the wall are video images of a watchful eye and the image of naked young man in an embryonic position. The falling drops break up the video projection into rhythmic light refractions. The images dissipate in concentric waves from one moment to the next, only to join together again immediately. The constantly changing projection becomes a symbol of human aggregate states. Just how fragile and process-dependent “human” in us and its dependence on processes are, is visualized with striking emotional immediacy. We experience the individual as wholly process-determined, as expressed, for example, by Gilbert Simondon or Bernard Stiegler: “The individual as an endless process of becoming."

Human states of aggregation

Christine Breyhan: Transformation, process, and the self in the process of change. Your perfect portrait in ice is recognizable only briefly in the exhibition. The melting process unfolds in front of a constantly changing audience in „Treibhaus Museum“ (Greenhouse Museum). Hardly anyone will be able to follow the transformation to the point of total dissolution. Irritation and confusion?

FK: Perhaps that is precisely why my transient works serve as an apt metaphor for “human aggregate states,” for the processes involved in individualization. In that sense, my art is very close to life. The individual evolves in a meandering biographical process. The stream of life is rarely observable in its entirety. And I like the concept of “Treibhaus Museum” in this context. Museums actually do “cultivate” thinking and help visitors understand themselves and their own present in order to devote themselves to a creative future. The growth of germinal cells is stimulated in the “Treibhaus.” Irritation and confusion are a natural part of that process.

CB: Unlike a bronze or stone sculpture, this work of art loses its form and dissolves away. Does this lack of constancy reflect the frailty of the conditio humana?

FK: I’m interested in the interdependencies, the determining conditions into which an individual is born, the steps in the development of a life, the opportunities and the non-existent equality of opportunity – in other words, the fragile aspects of human life, not what is safe and secure. By allowing my “body” to melt, I set something in motion that is very closely linked with life itself. It has something to do with letting go...

Issues of this kind became most clearly evident in the Existenzielle Bildwelten (Existential Visual Worlds) an exhibition presented by the Hamburg art collector Rik Reinking at the Weserburg in Bremen (2014). There, my melting torso was suspended upside-down on a chain hoist like a slaughtered animal being drained of its blood. In the same room, next to the frozen body, Tim Steiner sat on a pedestal and presented his naked back displaying the tattooed work by Wim Delvoye. An intense dialog developed between the living human being, the data medium that sells its own skin, and my melting ice-body that loses its human form.

CB: The process character of a temporal sequence is experienced through the senses. Can one identify a phase of your life in each manifestation of the work of art?

FK: Although the forms of the head and body are based on my own image, I was not the focus of the work. I thought the portrait was a valid and clearly decipherable symbol of our Western culture. Examples of that can be found in profiles on coins, classical busts, and the portraits of members of the ruling class. Heads represent our cultural history. When my portrait bust melts, a chain of cultural-historical associations is exposed. My head was merely the model, the material that was always readily available to me. Parallels with my life and artistic freedom become apparent only in retrospect.

CB: There is something metaphorical about the process of observing how the contoured facial features of your portrait are blurred, dark spots form on the melting ice-body, the work melts into a pool of water on the floor. One might even find it threatening.

FK: I tend to find it pleasurable. There is always an intimate, sexual aspect involved whenever I see myself melting in public - the way the different aggregate states follow each other in sequence, from the explosively crackling and cracking body at minus 30 degrees to the accumulation of rime in the warm air of the museum. The furry, delicate body hair that grows on my work along with the rime, the traces left by the touches of visitors, the spots and changing colors that appear during the melting process, and the crystalline translucence of my own body... I find that all rather erotic. Surrender and dissolution are extremely sensual aspects of my art, and they charge each work with sexual energy.

CB: Melting, melting away, crossing boundaries: Foucault describes sex as the “universal key to self-discovery and self-interpretation.”

FK: Yes, (smile) ...Mr. Foucault always hit the nail on the head ... As an idealist, I also think that understanding and self-knowledge always begin in something immediate, in an inexorable intuitive energy that is far ahead of conscious thought. I think that sex and ecstasy are very closely related to the creation and experience of art.

CB: What happens to you when your “self” dissolves into a shapeless, amorphous, watery nothing?

FK: “Losing face” always has something to do with honesty. There is nothing worse than politicians and business moguls who are intent only upon “not losing face.” I’ve been losing my face regularly in Europe since 1990. And I always gain something new in the process! As the face melts, my portrait passes through the stages of all of the formal languages of the history of sculpture - from the realistic figurative bust to the various degrees of abstraction to total dissolution. It all revolves around de-formation and re-formation. Francis Bacon had a formative influence on my image of mankind and my concept of art: “Reality is pain.” All strength also has a painful component. We are fragile and full of longing. That is why we love art. It offers us an explanation for what is “human” in ourselves.

CB: Before we close, I’d like to mention the aspect of irritation that Adorno attributes to art as a whole: “The fact that works of art say something and deny it in the same breath identifies the character of the enigma under the aspect of language.” And artists’ practice of depicting something only to conceal it from our eyes because they reject the visibility of the work need not be seen as a contradiction. But what is it? Is it fortitude, denial of easy consumability, or a form of behavior designed to stimulate the imagination?

FK: Perhaps it is a variation of the sensual manifestations of art, the pleasure that comes with doubt and the joy that is experienced in questioning the present. Every enigma has an irresistible attraction and inspirational power. We are often more fascinated by what we cannot immediately decipher than by what we clearly recognize. It awakens our curiosity and tickles our imagination. The power to imagine one’s own horizons and the worlds of others is heightened. And in those ideal cases in which the enigma is combined with humor, I am always happy to give in to the interplay of the spoken and the unspeakable. I think the fact that works of art say something and deny it in the same breath truly has a great deal to do with the erotic. Perhaps Adorno would not disagree!