- Current projects

- Selected Works

- Häutungen und Metamorphosen

- Ex vivo - in vitro

- Sammlung Reinking Hamburg 2011

- Kunstmuseum Bern 2013

- Kunsthaus Zofingen 2017

- Mess Up Your Mind

- Mon crâne retrouve son propre visage

- Kunstgeschichte kitzelt

- Ataraxie & Eudaimonia

- Choreography Bern Ballett 2007

- Kunsthalle Bern 2006

- Aargauer Kunsthaus 2021

- Ali Baba und die 40 Kunstkritiker

- Alphons Silbermann 1999

- Art and War 2003

- Weserburg Bremen 2014

- Kunstverein Ruhr 2015

- Echo and Narcissus 2012

- Facing History 2019

- Rede mit mir

- The Artist

- Bibliography

- Lectureships

- Contact

Kairos and Chronos

Peter Friese, Thoughts on the Performative Installation by Franticek Klossner

Kunstverein Ruhr, Essen, NRW, Germany, 2015

The Bern-based Swiss artist has created a striking multipart installation for the exhibition space of the Kunstverein Ruhr. It is comprised of two video projections as well as a frozen self-portrait made of ice that actually melts in the space. The combination of state-of-the-art media technology and performative and sculptural elements facilitates an aesthetic experience within which collective visual worlds are superimposed with contemporary thought and undergo an exciting update. The strange title of the exhibition furthermore takes up two concepts that stem from antique Greek thought that shall confirm this point of departure and the ensuing lines of thought.

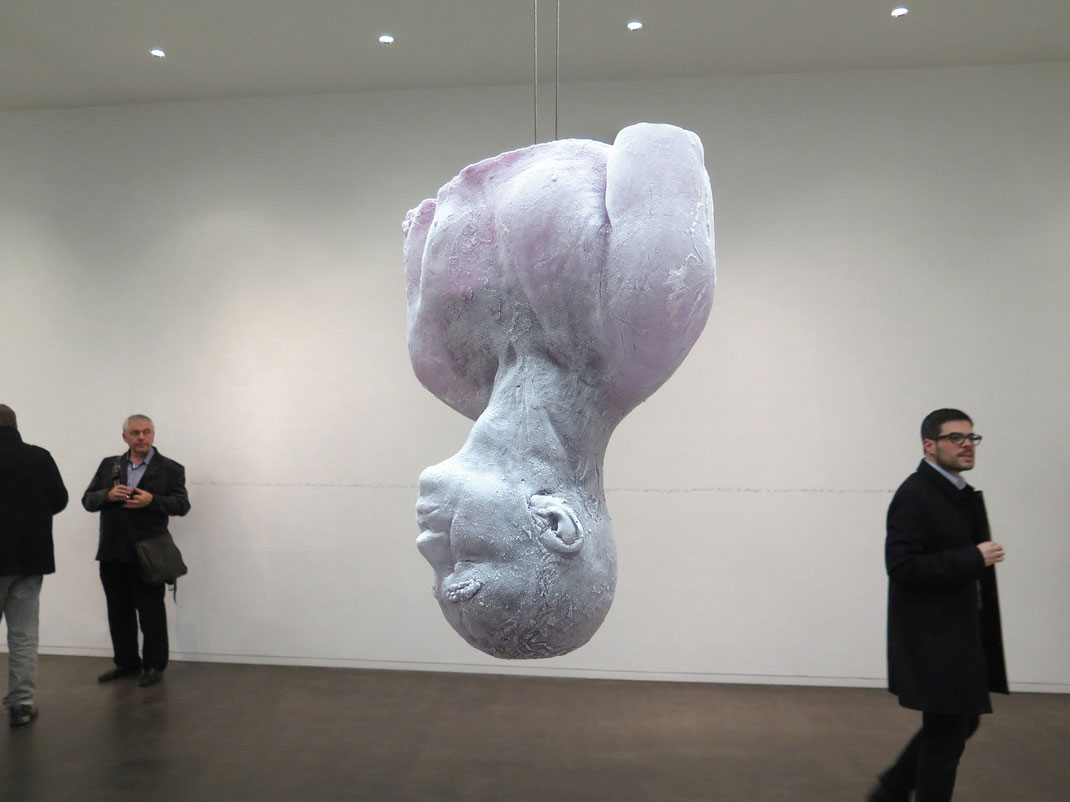

Melting self-portrait

A self-portrait of the artist made of ice hangs above a large surface of water that has been placed on the floor of the exhibition space. It is initially an exact one-to-one cast of the artist’s head. Just out of cold storage and hung upside down on a metal loop, this impressive body of ice initially becomes covered with a velvety white layer of frost before it gradually begins to melt and drip off due to the ambient temperature. This physical process occurs in what for the viewer is amazing slowness, which in turn demands one’s awareness. The waiting time becomes part of the performative concept. The fine white ice crystals ultimately dissolve, and the melting process can be experienced as a permanent rhythmic process within the exhibition.

Image and counterimage

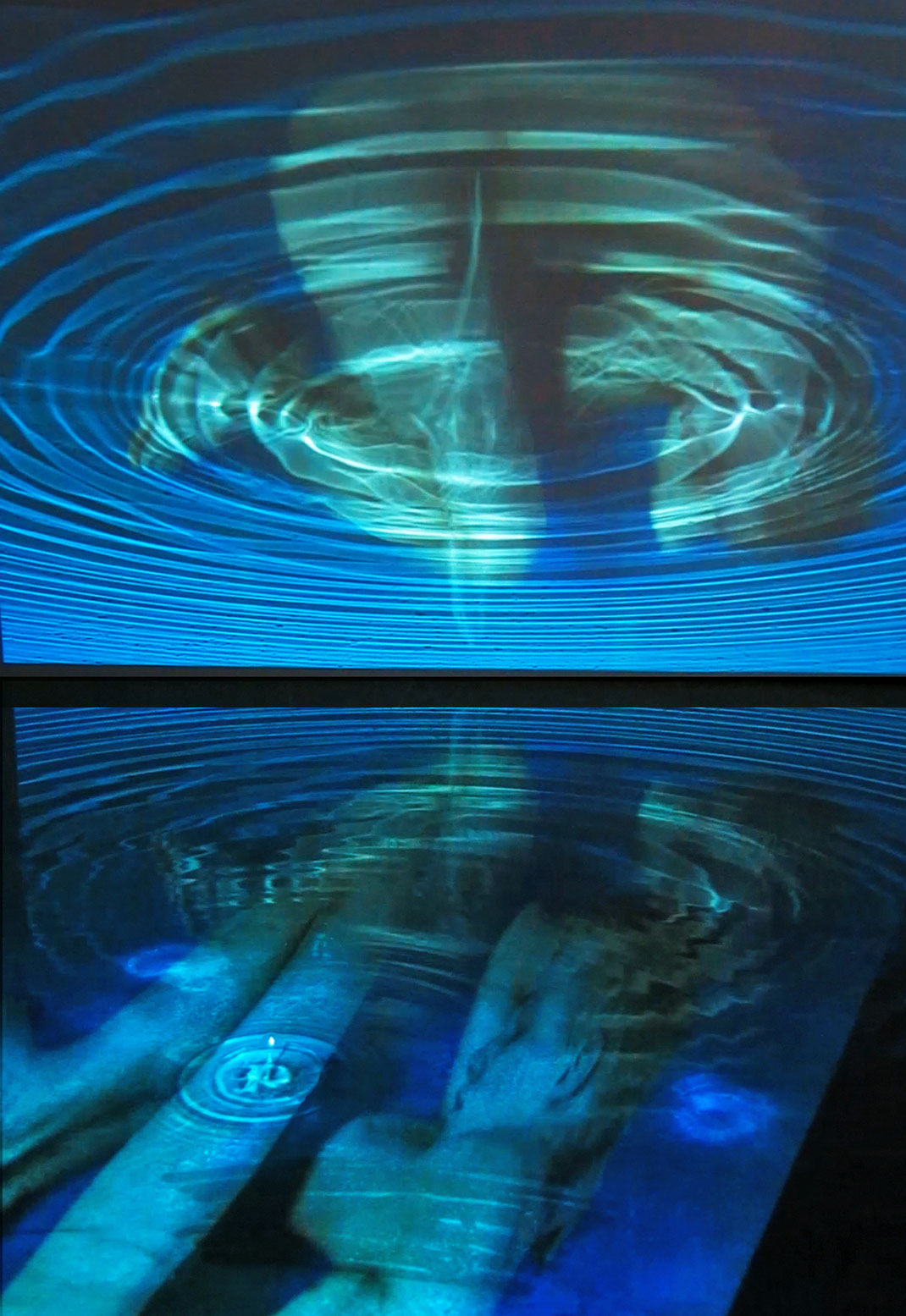

Alternately projected onto the water is video footage of an attentive eye and the image of a naked young man in a fetal curl. A video projector was placed in such a way that these images are reflected from the surface of the water onto the opposite wall of the space and enlarged. The drops of water constantly falling from the melting head, however, produce concentrically pulsating circles on the surface of the water, like individual raindrops on a lake. And because the video projection is a “light image,” these waves create multiple light refractions and visual amplitudes within the image mirroring. An impressive, constantly changing situation develops—both on the surface of the water as well as in the actual video, into which the viewer is automatically integrated. It looks as though the viewer’s gaze is responded to by the counter-gaze of the large eye, which the curled up body of the naked young man then follows. And all of this is permeated by the dynamically concentric circles and oscillations emanating from the drops of water to ultimately condense into a striking overall image.

Performative installation

Frantiček Klossner describes his series with frozen portraits and bodies as an “infinite performance.” The performative concept is not only laid out for the duration of an exhibition; he applied it as early as in his first “freezings” (1990) and continues to do so to this day, each time in a new context, in numerous installative or media variations. Each new staging is a temporary process in which the viewer involuntarily participates. Hence it is not just about the coexistence of images layered one over the other or about the portrait made of ice that slowly melts, but also, and above all, about interpenetration and overlaying in a conceptual, aesthetic sense. The elements placed in the exhibition space depend on each other and in their entirety are in a position stimulate thoughts, feelings, and memories whose coexistence is already art-specific. The rhythmically moving video image and the ice head prompt meditating on time that is trickling away, one’s own lifetime, and impermanence. The fact that the material used to create the head is frozen water, which melts over time, makes it an ephemeral “human image” that visibly changes over time and ultimately dissolves. This “always-becoming-less” of the solid, icy substance and the gradual dripping away of the melt water thus belong to Klossner’s understanding of the work and his concept. A temporary sculpture, so to speak, an image undergoing permanent dissolution that is capable of prompting multiple, by all means contradictory associations in the viewer. In actuality, what is occurring here is a completely normal physical process for the purpose of demonstrating the transformation from a solid into a liquid aggregate state. Yet Klossner is not concerned with a scientific test arrangement but with a work of art and thus a polysemous symbolic placement and with the conscious reactivation of millennia-old concepts of time. The artist is furthermore concerned with the palpable generation of a concept of humankind that embodies time, as it were, and thus in terms of its theme is also concerned with the existential question as to an individual’s “internal time” and “external time.”

Kairos - Chronos - Aion

The title of the exhibition thematically takes up two different concepts of time discovered by the Greeks. Chronos as passing, permanently trickling away, linear, and thus also quantitatively measurable time on which we, as individuals who live for only a limited period of time, count and which we have to “get over with” in both a figurative and a literal sense. It is about the time we have at our disposal, hence about the time that remains. Archaic Greeks personified Chronos as the primordial god who emerged directly out of chaos. He ultimately created the world as we know it and with it our concepts of time and mortality as well, to which we are subjected in the end. By contrast, Kairos embodies a completely different Greek concept of time. We can understand it as a propitious, appropriate point in time to, for example, make a right decision. Or as a convenient coincidence of several components that are essentially independent of one another. We can, indeed we must actively take a stand on Kairos in order to seize it at the right moment. It is about a notion of time that one takes when one recognizes the right moment—in order to take advantage of it. The Archaic Greeks visualized Kairos as a very agile, handsome young man with a forelock. And in terms of the anthropomorphism they practiced, in a proverbial sense it is also about quickly and resolutely seizing this time. In German there is the word “kairophobia,” which is borrowed from Greek and appropriately stands for the “fear of making decisions.” Kairos is also regarded as the youngest son of Zeus, and because of his youth and handsomeness embodies precisely the timeliness in question, the moment, which can soon be over. For the Greeks, these two concepts of time constitute an opposing pair that still possesses plausibility: the time that one has normally distinguishes itself completely from the time one takes. Time objectively measured by a chronometer is something completely different than subjectively perceived or consciously experienced time. Hours sometimes pass as quickly as minutes, and vice versa. For the sake of completeness, Aion should be cited as a third component of time. For the Greeks, its lion-maned, winged embodiment stands for eternity. Hence for a concept of time that surpasses chronologically measurable life time and its available propitious moments, and which is beyond our imagination and thus also makes palpable the boundaries of our understanding. Yet the Greeks were capable of imagining Kairos and Aion touch and making the possibility (that sometimes shines out in art) last eternally for a moment, or at least appear to last eternally. The installation accommodates these different concepts of time to the extent that the reclining young man in the video could symbolically represent a contemporary Kairos. The embodiment and staging of the moment, so to speak, whose image is overlaid by the relentlessly falling drops of Chronos and is ultimately obliterated.

The activation of internal images

Frantiček Klossner’s entire oeuvre deals with existential themes. It is about socialization and individuation. And the human body, its beauty, yet also its frailty and mortality time and again play a key role. All of these themes reconnect in our collective visual memory. And this insight is a key to Klossner’s oeuvre, as it were. The images that he creates in his performative installation obtain their evidence precisely through the deliberate use of collective imagery. In other words: Klossner is not the sole “inventor” of these visual concepts but their conscious user, participator, and interpreter. He uses the cultural visual memory in his work that has already existed for thousands of years and generates contemporary and binding images of our time. One could also speak of efficacious images, which in terms of Aby Warburg open up a calm space of thought in the viewer. And here, the melting self-portrait provides a large quantity of material. Marsyas, who was maltreated by Apollo, an image anchored in our visual memory, also occurs to us, as do scenes of torture from the Vietnam War, decapitations by guillotine during the French Revolution, or the recent beheadings of innocent hostages by religious fanatics that have recently circulated in the Internet.

The reversal of time

Let us return to the performative installation at the Kunstverein Ruhr. There is a second video projection in the front area of the exhibition space in which an ice portrait melts in quick motion, only to—turning back time—resynthesize, and then only to melt again afterwards. This staging confronts the viewer with a concentric symbol: played back as a loop, the video becomes a symbol for becoming and passing, for a never-ending, permanently recurring process that qua quick motion can be grasped in its inescapability. Both components complement one another; in the exhibition they become opposites that endow meaning.

How meaning comes about and the one is related to the other

As we could demonstrate, Klossner is concerned with symbols whose meaning lies on a deeper symbolic level. The Greek sumballein, from which “symbol” is derived, literally means “to throw together” and thus expresses the multilayeredness and complexity of complementary levels of meaning. But how do these meanings come out? Is “meaning” inherent in symbols per se, or is it given to them? Klossner’s use of such “strong images” does not occur in the sense of a restaging of eternally valid archai, as a certain school of thought would suggest. They are not “archetypes” that are believed to last eternally and always have been and will always be independent of civilization. Instead, Klossner uses vivid consolidations of images of conflict from our cultural history. These images are constructed by human beings over the course of history and are considered relevant. It was not until their permanent reconstruction, recollection, and reconnection that they became what they represent to us what they do today.

Mythical state of mind

In view of these “strong images,” Aby Warburg would also speak of a surplus of energy, of a potential inherent in them, and that only certain images—among which I would also like to count melting self-portraits—possess them of their own accord. Yet as already said, this visual energy is not available eternally and God-given, but first develops in the civilization process, has inscribed itself into the images, so to speak, and in them has achieved imagination, as it were. In this way, it could at the same time also become part of different myths, which these strong images communicate, among other things. If one understands myth as a narrative that is independent from its originator, hence as a story that must have developed a very long time ago and has since been time and again handed down and told (with constant modifications and supplements), a relationship between art and myth may be assumed here that dates back far into the history of humankind. Klossner is aware of these far-reaching relationships and takes them up in his work in a special way.

Aesthetic experience

These collective images that have inscribed themselves in our memory and the recollection of their associated narratives are revealed, are retrieved, so to speak, by means of the thought-out use of modern media technology. Amazingly enough, at the same time several levels of time that overlie one another play an important role. Firstly, the constantly recurring time loop preserved on video, one that alternately shows up the large eye looking at us and the bent, naked male body, and in the second video the head of ice that melts and then resynthesizes. And secondly the time actually passing in the space, which we become aware of through the ice skull dissolving before our eyes. In this case it is the permanently falling drops of water and the concentric circles they generate that makes us aware of time actually dripping down in the space, much like the water clock, the clepsydra, common among the Greeks. A proverbial work in space and time that knows how to address time and its associated levels of meaning. By discovering these relationships and referring them to ourselves, we transfer the process of seeing, observing, and associating into aesthetic reasoning.

Dissolution and presence

The overall work becomes a lasting, strong image, precisely because it changes before the viewer’s eyes to completely dissolve and, as already mentioned, works with different levels and time and images. The opposite directions of disappearance and retaining in memory are a special feature of the work, and at first glance it can almost be understood as an apparently paradoxical trait. In a stricter sense, it is about becoming aware of a simultaneously occurring dematerialization (melting) and etherealization (remembering), which are elements of the aesthetic experience associated with this work. Jochen Gerz once said that true images are those that are not images. What he means by this are the internal images that have their place in our ideas, our memories, our desires, and our fears. These images are inscribed in Klossner’s work and invite the viewer to meditate, and precisely because they are so potent at the same time to reflect and understand.

The human body in contemporary art